Unearthing the Seeds of Black Power

How former slaves became a political force

by Eileen Fisher

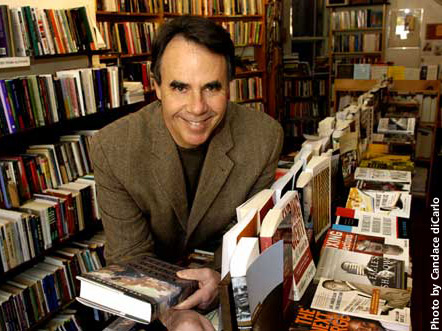

For historian Steven Hahn, the inspiration to write A Nation Under Our Feet, the book that would win him the Pulitzer Prize, came early on in his careerówhen he was diligently pursuing something else.

Hahn was researching labor relations, the subject of his dissertation, when he came upon a set of records from the Freedmenís Bureau (a federal agency that had overseen the transition from slavery to freedom), which had just become available on microfilm. "I began reading reports about African American freed people in the 1860s who were leaving their work and walking 25 miles to political meetings. I was really stunned by this," he says, recalling that the historical literature at that time viewed 19th century blacks as either apolitical or pawns of whites. "But it was clear to me there was no way this could have developed just in the year and a half that had passed since slavery ended." So began his doubts about the "liberal integrationist framework" that regarded the struggle for freedom not as a movement blacks generated, but as one delivered to them.

his hunch, Hahn says, this suspicion of a bigger story only hinted at by what he found by accident led him to dig deeper into the historical records. ìMore than anything else Iíve worked on, it was the work in the archives that shaped my thinking [for this book], that generated more questions. It was really research from the ground up as well as history from the ground up,î he says of the book, subtitled ìBlack Political Struggles from Slavery to the Great Migration.î And when he began to dig, he found ample evidence that political activity during slavery and early emancipation were formative to later black politics.

Hahn found plenty of evidence to show that even rural slaves understood the political struggles of their time and responded actively. Upon Lincolnís inauguration, 17 slaves on a plantation just outside Petersburg, Virginia, toasted the occasion by declaring their freedom. Many deserted their farms and plantations during wartime; widespread slowdowns and resistance to work, reported by planters whose slaves stayed, are further evidence that news and rumor circulated quickly and widely among African Americans of the time, uniting their actions.

Bound by kinshipósome family, some adopted ìrelationsîóAfrican Americans had long conducted societies of their own, where elders mediated disputes and where groups negotiated privileges and rights, bargaining with their masters. By the time of the Civil War, the black churches were a forum for political organizing, grooming leaders for the freedmenís conventions of 1865.

In the turbulent reconstruction of the South, African American agitation was a major factor. Republicans acquired a mass base in the South, but without land reform, blacks remained dependent and could be manipulated politically. Still, with organizationólabor squads that acted as political groups, ìcommitteesî that negotiated labor and did military drillsómany blacks defied the threats of white Democrats and registered to vote. Their struggles for political power were centered in the Republican Party and in Union League chapters.

Many politically active blacks lost jobs. Black power also was countered by laws that stipulated county officers had to post bond to take office, a prohibitive expense for families struggling to survive. And black elected leaders often were threatened outright and even killed.

Not all in the black community were united in response to these conflicts. Some promoted emigrationism, suggesting movements to Liberia, or to Kansas or Indiana. Opponents of that idea didnít want to give up on labor efforts, especially in the South. Where white farmers joined in race-exclusive Populist groups to counter tariff and banking policies that favored the industrial powers of the North, blacks joined the biracial Knights of Labor and the Colored Farmers Alliance. But the organizing impulse behind emigrationism was itself a positive force and a base for later activism, says Hahnóleading into the era of Booker T. Washington, the Great Migration, and Marcus Garveyís pan-Africanism.

With gerrymandering, poll taxes, and local qualifications for voting that excluded many blacks, landowners' rights were promoted; sharecroppers and other tenants became more dependent. Jim Crow laws, by the turn of the century, meant the end of Reconstruction. Still, civic and association life in the black community, which flowered in the last decades of the 19th century, laid the groundwork for the Great Migration north, from 1915 to 1930. And the groups that followed served as precursors for later political organizing. Elijah Muhammed and Malcolm X both hailed from Garveyite families.

Hahn adds that revelations about the slavery and early emancipation periods also offer broad and lasting lessons about the issue of class in American politics, about how hard it is for working people to express themselves politically. "On the one hand, it is incredibly moving what people are willing to do and willing to risk, and it can make a difference," he says. "Even so, the obstacles they face are enormous."

"Blacks would get elected, and theyíd get assassinated. Or they couldnít post bond. Or a mob would run them out of town. This is even after they succeeded in the electoral process. Winning power and taking power are two different things," he concludes.

Eileen Fisher is a freelance writer and editor in Philadelphia.